The need to leave a mark: Cuddy's Cave

Most of us know and importantly follow the concept of ‘leave no trace’ when visiting, frankly, anywhere. But, as we’ve all seen over the past few years, many don’t know or do know but don’t follow the memorable mantra. Sadly, a trip to St Cuthbert’s Cave this weekend was yet another example in a growing list. For some reason, this stuck out to me more than others, maybe because when you look closer at the cave, it’s littered with the marks that humans feel the need to leave.

First, indulge me in a bit of background…

Cuddy’s Cave is formed of that beautiful soft-looking sandstone, a rock synonymous with Northumberland from the Simonside hills to the buildings that line Newcastle’s Grey Street. Deep fissures and grooves in the rocks give away hints at their formation over 330 million years ago, covered by a braided river system that carried great swathes of sand. These are formidable natural marks, ones you trace with your eyes and marvel at the shapes they form.

But then come our marks.

Legend has it that in 674, St Cuthbert retired to the cave to start life as a hermit, before moving to the Inner Farne island. Later, in 875, his body revisits the cave as it is used as a place of refuge for monks fleeing the infamous Viking raids, who take his tomb after seven years of wandering, to Chester-le-Street. It’s likely that as Cuthbert’s popularity in Northumberland increased throughout the medieval period (thanks to frankly excellent miracle working at battles) that this cave slowly became a place of pilgrimage, the same as Holy Island and Durham Cathedral. But its history is shrouded until at least the 13th Century when land rights, including the cave, are transferred from the Howburn family to the monks still residing on Holy Island. The next ‘fact’ we have is that in the 19th Century it was used as a lambing shed. But, between the Howburn family and the lambs, we find marks.

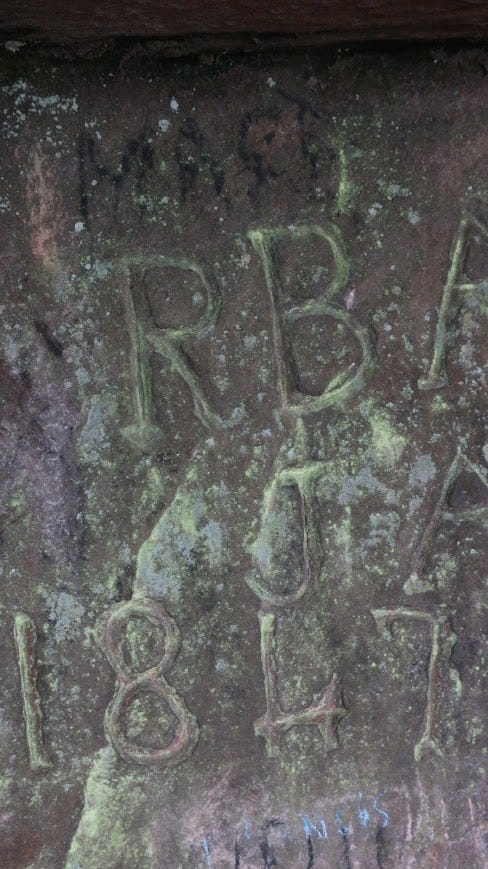

The earliest piece of graffiti that can still be read is one from the 1700s, and the etchings continue through the 1800s, 1900s and the 2000s. Sure, there’s a history in these marks, but to what end? What purpose other than to say ‘I was here just like you are now’?

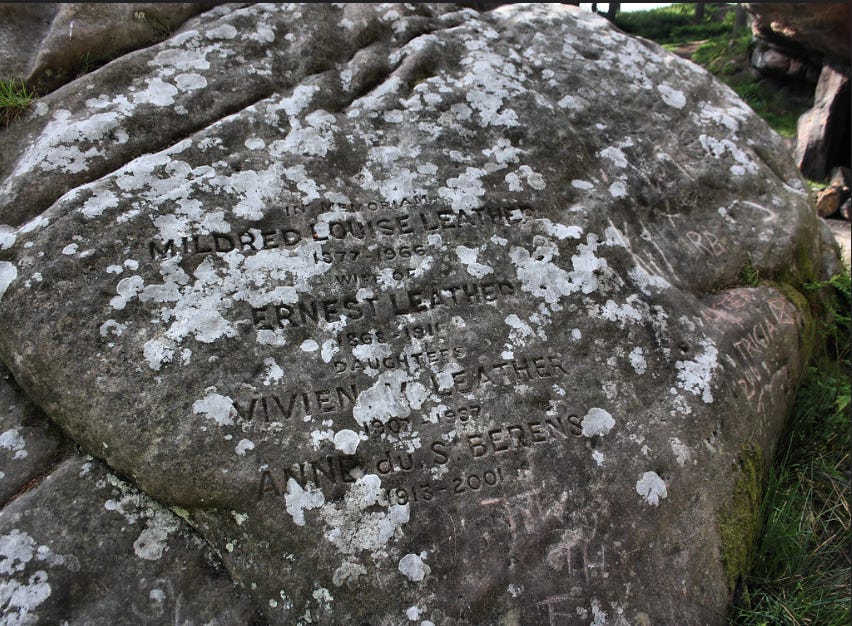

In 1936, the land around the cave was consecrated for the family burial of the Leather family, so carved deep into standing stones are memorials.

In 1981 the land is given over to the National Trust. We see their mark in signage on gates, reminding us of the Countryside Code: stick to the paths, no camping, no litter, no fires. They also more positively signpost what nature thrives around the cave: adders, red squirrels, yellow hammers, and goshawks. A reminder that it’s a living place.

We notice the smoke billowing between the Scots pines as we enter through the gates. We naively (perhaps hopefully) consider it’s maybe just plumes of chalk from enthusiastic boulderers that we had spotted leaving the car park just before us. The boulderers are, however, on the other side, stretching and laying out their mats and looking across the cave in slight disbelief. Behind the two standing stones at the entrance to the cave is what can only be described as a campsite. Camping chairs, bags of rubbish, and a smouldering fire set deep against the stones.

Please don’t misjudge me here. I have no issue with wild camping. None. In fact I love it, and railing against the restrictions we have against it is a post for another day. But I will always encourage those who do wild camping to do it safely, discreetly, and respectfully. For me, that means cleaning up and clearing out early on. It means no fires that will scar and threaten the landscape. It means considering the site where I intend to lay my head. It means leaving no trace.

It means leaving no mark.

Something St Cuthbert’s Cave is pitted with.